We’ve all experienced the calming effect of looking at flowers or the refreshing sensation of inhaling the scent of trees. Professor Yutaka Iwasaki from the Graduate School of Horticulture is working to scientifically uncover the reasons behind these phenomena, with the ultimate goal of fostering a society where everyone can maintain their health through interactions with plants.

Exploring the anti-stress benefits of plants

Could you explain the field of your specialty, ‘Environmental Health Studies?’

Environmental Health Studies examine how plants influence human health and well-being. Have you ever felt a sense of peace or comfort when surrounded by nature? A typical example of this concept is Horticultural Therapy, which we aim to validate scientifically and promote for widespread use in society.

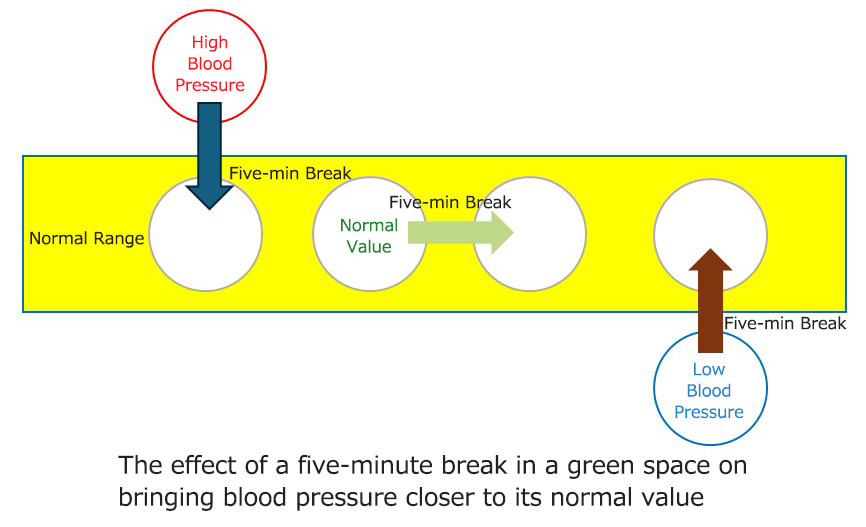

In one study, we placed a chair in a park surrounded by plants and measured participants’ physiological responses before and after sitting and resting for just five minutes. Regardless of their initial condition, we observed that their blood pressure moved closer to normal levels (Figure 1). This demonstrated that engaging with plants helps regulate homeostasis*—the body’s natural balance. When this study was published, research on the health functions of plants was limited, and our paper was the first to provide evidence showing plants can help restore physical condition to a near-normal state.

*Homeostasis: The body’s mechanism for maintaining stable physiological functions necessary for survival in response to internal and external changes.

There are many other great aspects to consider. While pets are a common source of comfort and healing, they can also bring stress, such as the daily responsibilities of care or the emotional toll of their loss. In contrast, growing plants offer a different kind of solace. Even if a plant withers, it encourages forward-thinking and problem-solving, like wondering, “Maybe I didn’t use enough fertilizer?”. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, gardening became very popular, likely because it offered people a sense of hope and something to nurture for the future.

I also decorated my home with flowers during the pandemic. What inspired you to start researching horticultural therapy?

Around the year 2000, I started exploring this field after personally experiencing the restorative effects of spending time in the forest as a student. At the time, there were no academic societies focused on the benefits of plants, and my research faced challenges. Papers were often rejected—those in plant sciences argued they could not evaluate effects on human health, while those in medical sciences claimed they did not understand plants. Despite these hurdles, I persevered, and over time, more researchers came to recognize and support my work. This gradual acceptance has allowed me to continue and expand my research to where it is today.

You are indeed the frontier of horticultural therapy. What has kept your passion alive for over 20 years?

I firmly believe in offering simple, practical ways for people to maintain their mental, physical, and social well-being in everyday life. For instance, in the park experiment I mentioned earlier, I was very deliberate about setting the duration to just five minutes. If you are told, “Sitting for 60 minutes is effective,” the act of sitting for 60 minutes itself could be a source of stress, and few would find it feasible. That’s why keeping it to five minutes is so important.

Also, while forest bathing has proven benefits, accessing a forest is not always practical for those who live in urban areas. This is why I introduced the concept of ‘park bathing’ and conducted experiments in nearby parks, aiming to achieve similar benefits as forest basing. My driving motivation is to contribute the findings of my research back to society. This sense of purpose ensures there’s always more to explore and new questions to answer—I feel my journey in this field is endless.

“Pickable flower beds” revitalize the community

Are there ways to work with plants that can enhance the effects of horticultural therapy?

In horticultural therapy, activities like ‘growing’ and ‘harvesting’ play a crucial role. These activities tap into fundamental human instincts rooted in our history as agricultural and hunting societies. For example, picking mandarin oranges is not just about consuming them but also about experiencing a sense of accomplishment and joy through the act of harvesting and hunting. Similarly, wouldn’t it be more fulfilling to pick flowers you have grown yourself to decorate your home or to harvest herbs and use them in cooking? From this perspective, I advocate for the concept of the ‘Garden of Use.’

What is a ‘Garden of Use’? Please tell me more.

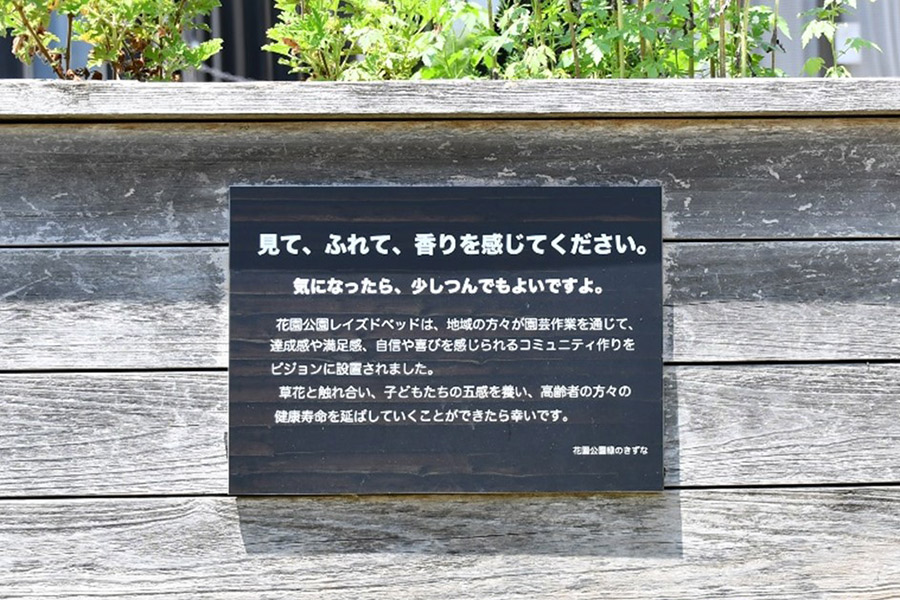

Hanazono Park, located about 200 meters north of JR Shinkemigawa Station, is a busy area where many people pass by on their way to the station. However, the park lacked a sense of community attachment, which led to issues like illegal garbage dumping. A local NPO approached us for advice, and in response, I proposed the ‘Pick-Your-Own Flower Beds: Hanazono Park Raised Bed Project.’ This initiative involves installing raised beds in the park to allow people to pick flowers and herbs as they pass through. The herbs are chosen for their ease of maintenance, appealing pleasant aroma and taste.

What kind of response have you received from the city and local residents?

Initially, we faced significant challenges, with resistance from various directions. There was no precedent for a ‘flower bed where visitors can pick the flowers,’ which made obtaining approval from the local government quite difficult. The city eventually agreed, but only on the condition that we gained the support of the local community. However, the neighborhood association was hesitant as well. To address their concerns, I organized a public meeting to share my vision. Slowly but surely, residents began to understand and support the idea, and we finally reached a point where implementation became a realistic possibility.

What was the residents’ reaction once the project began?

At first, even though they were encouraged to pick herbs, most people hesitated—it felt contrary to social norms. To ease this, I organized a simple workshop on how to use herbs, such as adding them to hot water to release their pleasant aroma. Gradually, people started thinking, “Maybe I’ll give it a try,” and began picking herbs. Over time, a sense of community involvement grew, with residents even taking the initiative to water the plants.

On a recent visit to the flower beds, I noticed that flowers had replaced the herbs. Curious, I asked why and learned that a local grandmother had mentioned, “I want to offer a flower to our household Buddhist altar every day, but I feel awkward buying just one flower from a florist.” Inspired by her comment, the community decided, “Let’s grow flowers for the alters.” After many trials and errors, this project was honored with the Community Grand Prize at the 31st Green Environmental Plan Awards by the Organization for Landscape and Urban Green Infrastructure. I am genuinely delighted that we have created a space where the local community can come together and flourish through the simple joy of ‘flower beds that are OK to pick.’

Horticultural therapy for caregivers

I heard you utilize Horticultural therapy in medical settings.

Simple gardening activities, such as thinning out vegetable plants*, can serve as an effective alternative to traditional rehabilitation exercises for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In palliative care for cancer patients, allowing them to choose their favorite seedlings—even while lying in bed—can provide a sense of calm and a connection to society.

However, since horticultural therapists are not medical professionals such as doctors or nurses, their direct interaction with patients is often limited, which has made it challenging to incorporate horticultural therapy into traditional medical practices. To address this, we have developed and are actively promoting a concept called ‘indirect horticultural therapy*’ for medical professionals.

*Thinning: The process of removing densely packed plants that have sprouted.

*Indirect horticultural therapy: A term coined by Dr. Iwasaki, referring to horticultural therapy directed at caregivers (e.g., nurses) rather than patients. By improving the well-being of caregivers, this method can also have a positive indirect impact on the patients they care for.

What inspired horticultural therapy for medical staff?

The idea for horticultural therapy for medical staff came from a personal experience. While visiting a palliative care ward to propose horticultural therapy, I was asked to wait at the nurse’s station. However, they were so busy that I was forgotten for a while (laughs).

During that waiting time, I observed many things. In the palliative care ward, I noticed that about three patients passed away each day. After each loss, families would come to express their tearful gratitude, and the nurses, also in tears, had to manage these emotional situations while continuing their demanding work. It became clear to me how mentally taxing their roles were.

I thought to myself, “I need to do something to relieve their stress.” This realization led us to quickly organize a gardening program for the nurses in their break room. Many nurses participated during their breaks, saying with a cheerful look on their faces, “I didn’t realize how calming it is to work with plants.” This was when I realized that “When nurses are stressed or tired, patients may hesitate to ask for help. However, if horticultural therapy can refresh and revitalize nurses, it might have an indirect positive effect on patients.” Indirect horticultural therapy does not require direct interaction with patients, so it avoids complicated procedures. It also provides much-needed stress relief for nurses, which has sparked growing interest in this approach across healthcare facilities.

Looking ahead, I believe this method could be applied to caregivers and aides in the nursing care field, as well as schoolteachers.

Taking on the challenge of creating spaces to support social health after retirement

What are your prospects for the future?

In Japan, people are often expected to dedicate themselves fully to their work. As a result, when individuals who have spent most of their lives for a company reach retirement age, they may suddenly feel disconnected from society, with few friends or places to go outside their home. Many elderly individuals experience feelings of loneliness and helplessness, leading to a loss of motivation and gradual withdrawal into isolation. The sudden lifestyle change after retirement is a major factor that undermines the social health of older adults.

To address this, I am exploring ways to utilize local farms as casual gathering spaces for retirees. These farms could serve as an opportunity for retired individuals to step outside. By growing crops, harvesting them to give as gifts to family and neighbors, cooking, eating, or finding other ways to participate, these farms could become vibrant spaces where people come to gather, have fun, and build meaningful connections.

With an increasingly aging population, I aim to explore the unexplored potential of agriculture and horticulture in enhancing social health.

My vision is to create a society where everyone can enjoy physical, mental, and social well-being through plants. Would you like to join us in spreading the benefits of horticultural therapy? I am actively delivering public lectures to share my research achievements in an easy-to-understand and engaging way. If invited, I am willing to travel anywhere in the world to promote this initiative.

● ● Off Topic ● ●

You look like you are having a lot of fun with your research!

I think it’s important to share the excitement of research with students. Plus, I genuinely enjoy exploring new ideas with them. Sometimes, they surprise me with incredibly original topics.

What kind of research topics have they come up with?

One student came to me wanting to research ‘mountain gods.’ Naturally, I was not familiar with the subject, so we started reading books and learning together. We then mapped out the locations of Hokora—small, simple structures built to honor and house spirits or gods, often found along roadsides— and overlaid the GIS data. To our surprise, we discovered that many of them were in areas where accidents were more likely to occur. It was a fascinating discovery that I would never have known about on my own!

Series

Fostering Community Connections through Gardening

Explore how our researchers’ initiatives in regional revitalization, health, and welfare are nurturing heartfelt connections between gardening and the local community!

Recommend

-

Viewing a Diverse World through the Lens of Agriculture and Food: Enriching Global SDGs Education with Insights from Extensive Overseas Field Research

2023.08.31

-

Creating a Flourishing Society with Novel Cultivars of Fruits: Integrating Molecular Genetics, Statistical Genetics, and Data Science for Efficient Fruit Tree Breeding

2023.09.08

-

Examining Social Injustice of Modern Society through “Child Poverty”: Creating a Society Where Every Parent is Respected, and Every Child Thrives

2023.05.26