Commencing in 2023, the ‘IAAR Seminar’ introduces the latest research efforts of Chiba University researchers, fostering profound insights. In the latest session, Professor Makoto Ichikawa from the Graduate School of Humanities delved into the captivating question: “Does the flow of psychological time slow down in moments of surprise? Subsequently, a psychophysical examination of ‘Tachypsychia’ unfolded.

‘Tachypsychia,’ also referred to as ‘slow-motion perception,’ manifests as a phenomenon where time perception undergoes fluctuations driven by our emotions. Typically, humans lack a sensory organ capable of measuring time as accurately as a clock. Then, how is time perceived and processed in human beings? Guided by Professor Ichikawa, who serves as the president of the Japanese Society for Time Studies and employs experimental methods to explore human perceptual-cognitive processes and sensibility characteristics, participants were enticed into a mysterious world.

Two types of time: time in the world of ‘Objects’ and time in the world of the ‘Mind.’

The term’ time’ has two realms: the objective ‘Physical Time,’ ticking away consistently and accurately like a clock. The other is the subjective ‘psychological time,’ stretching or shrinking depending on our mental state (emotions). Have you ever heard a story where someone facing danger, like in a traffic accident, says, “I saw the entire scenery in slow motion”? This phenomenon is known as ‘Tachypsychia.’

How do human beings perceive time?

Humans generally possess five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Unlike attributes such as ‘light-sight’ and ‘sound-hearing,’ which pair with specific sensory organs, time lacks a direct sensory channel. Consequently, perceiving precise aspects of time, such as the exact length and timing related to duration, sequence, and simultaneity, as ‘time itself’ proves challenging for humans.

For instance, while one can perceive the moment when a certain event occurs, directly sensing how long the event lasted or its temporal relationship (intervals) with other events is not possible.

In reality, the brain addresses this challenge by supplementing time-related information with data from visual sources. This process is called an ‘ill-posed problem,’ lacking a straightforward solution. The brain is considered to integrate diverse information and past experiences to form a concept of time.

The focus of today’s discussion is Psychophysics ―a field aimed at elucidating the brain’s mechanism of constructing the world, expressed through the perspectives of time in the world of ‘Objects’ and time in the world of ‘Mind.’

Tachypsychia, a phenomenon that has been considered an ‘Optical Illusion’

Tachypsychia, the phenomenon where time seems to move slowly, was once considered ‘a type of optical illusion not actually perceived in slow motion.’ There were reports suggesting that ‘strong fear accelerates an individual’s processing, recognition, and understanding abilities, allowing them to perceive detailed phenomena normally invisible under usual conditions. However, there were no experimental results replicating this claim.

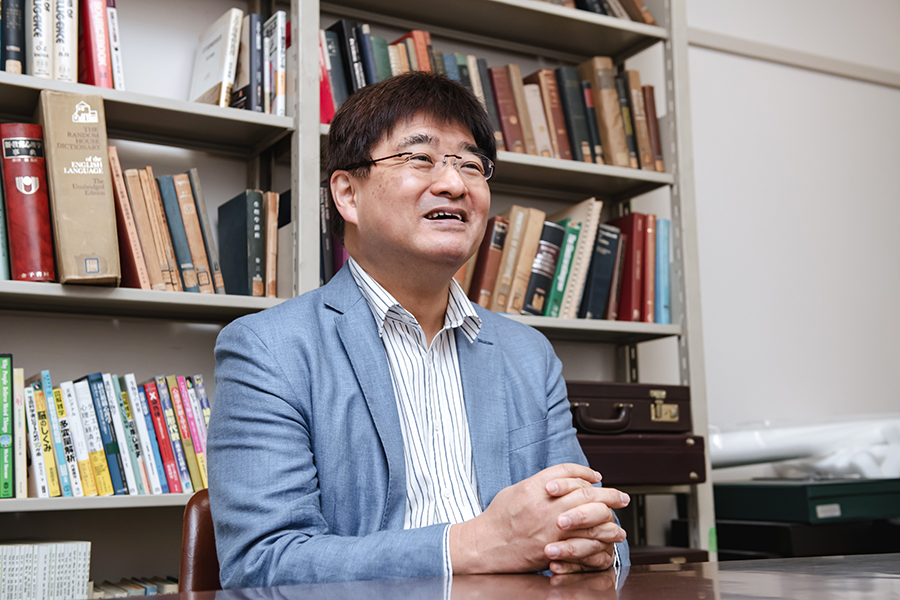

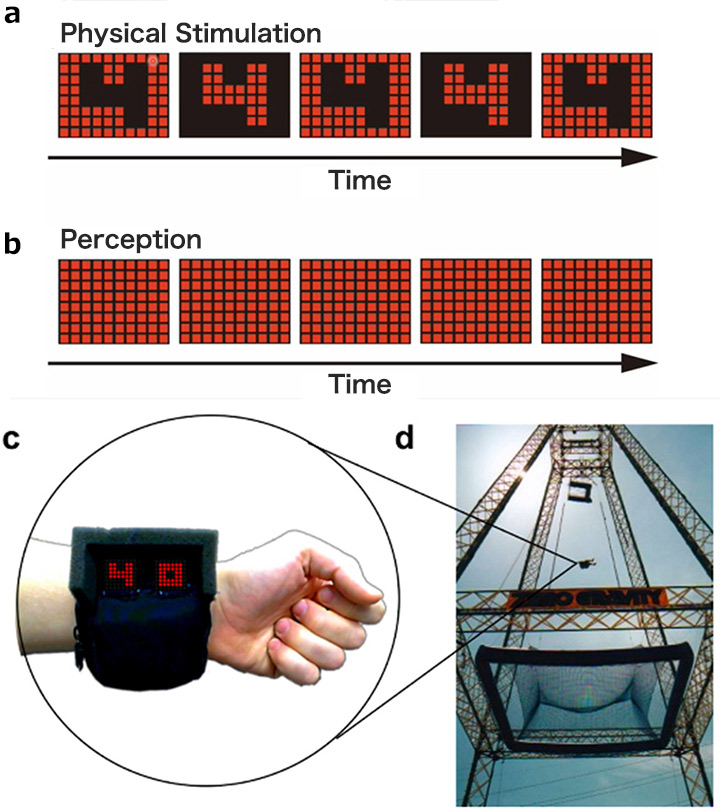

I would like to introduce a previous study that served as a catalyst for considering Tachypsychia to be an illusion. David M. Eagleman and his colleagues conducted an experiment using the Suspended Catch Air Device (SCAD), a thrill ride similar to bungee jumping without ropes (PLOS One, 2007). In this experiment, participants read numbers on a liquid crystal display before and during the fall. The display exhibits numbers against a background that rapidly alternates between red and black. As the speed of alternation increased, distinguishing between the numbers and the background became more challenging (Figure 1).

They hypothesized that “if fear enhances the perception of temporal precision, individuals should be able to read even at higher rates of text inversion.” To test this hypothesis, they conducted an experiment measuring the ‘Critical Flicker Fusion Threshold (CFFT).’ During the experiment, participants were assessed to determine if they could accurately read numbers displayed during an attraction at a speed slightly faster than the point at which participants could ‘barely read numbers’ before the attraction.

(Adapted from David M. Eagleman et al., Does Time Really Slow Down While a Frightening Event? PLoS ONE 2(12): e1295, 2007)

Participants reported that the duration of their fall felt longer. However, the experiment did not yield evidence supporting an improvement in temporal precision, such as the ability to ‘perceive text inversion faster than on the ground.’ Consequently, we now posit that what was initially considered a phenomenon is likely an illusion, influenced by the human tendency ‘to vividly recall peculiar events under the influence of fear and tension.’ This suggests that the perceived elongation of time during the fall may not be a genuine experience of slow motion.

The world’s first demonstration of the Tachypsychia

Ms. Misa Kobayashi, a graduate student at that time, and I noticed issues with the experiments conducted by Eagleman and his team. Therefore, our research group engaged in discussions and conducted a retest of Eagleman’s experiment in a laboratory setting using a method that addressed the following three issues.

① The observation environment was not ideal.

Participants were required to watch a display attached to their wrist while falling. It is desirable to have their heads fixed in a position where they can clearly see it.

② Emotional reactions were not confirmed.

SCAD is an amusement park attraction where safety is ensured. In an environment where there is no risk of injury, even if they fall, there is a possibility that feelings of joy and excitement outweigh the fear.

③ The number of measurements was insufficient.

In psychophysics, typically, trials are made for each condition in over 100 trials, but only one trial per participant was conducted.

We utilized the International Affective Picture System (IAPS), an image database developed by a research group at the University of Florida, to elicit emotions. We selected 12 images, each categorized as evoking feelings of danger and safety.

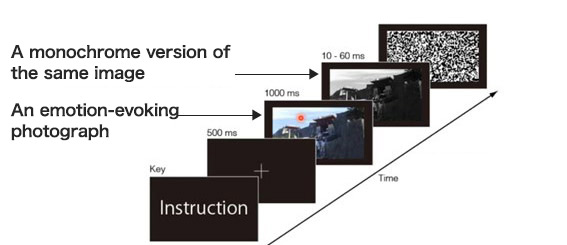

Following a one-second presentation of an emotion-evoking photograph, a monochrome version of the same image was displayed for 0.01-0.06 seconds. Participants were then asked whether they perceived the monochrome image (Figure 2). We conducted 144 trials under each emotional condition. This approach aimed to measure potential variations in perceptual abilities to extract information from monochrome images based on the level of emotional arousal.

IAPS provides nine levels of fear-inducing images, but we were unable to use the images with the highest intensity due to research ethics. Instead, we employed moderately dangerous images, such as those depicting snakes. Even with these images, we observed an increase in visual temporal accuracy by approximately 10%, confirming a globally observable Tachypsychia (2016).

Does emotion improve time accuracy?

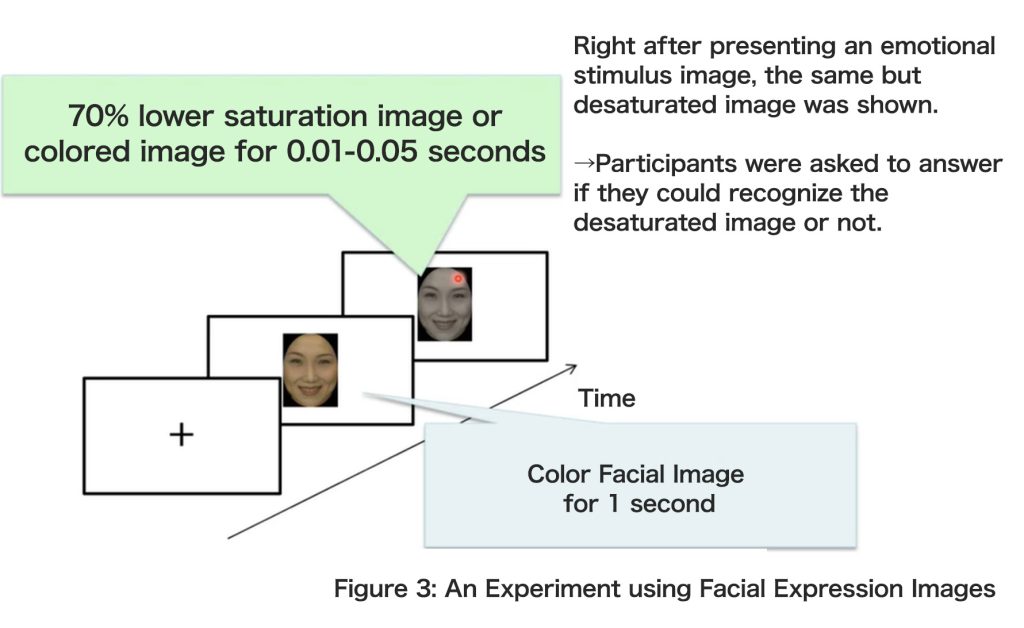

Our previous experiment used images in natural settings, including living creatures, leading to speculation about the potential impact of their characteristics, such as luminance or color distribution. As a result, we conducted further experiments using human facial expression images, as detailed in our study published in 2023* (Figure 3).

*A still image database of facial expressions developed by the Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International (ATR) as an emotional stimulus for facial recognition research.

The stimulation conditions were as follows:

- Four types of facial expressions: joy, anger, fear (high arousal), neutral

- The individual in each image: Two males and two females

- Image orientation: Upright (normal position) and inverted (flipping the image upside down to make discerning facial expressions more difficult)

- Presentation conditions: A color image is presented for one second, followed by the presentation of a monochrome image

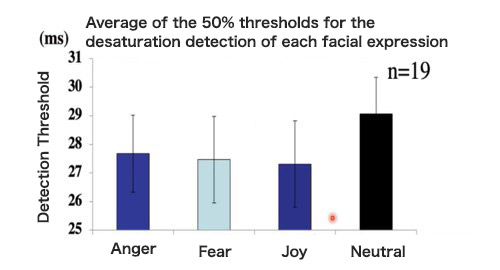

Compared to the neutral image, three images showed improved time accuracy, resulting in faster recognition

Not much difference recognized among the four images

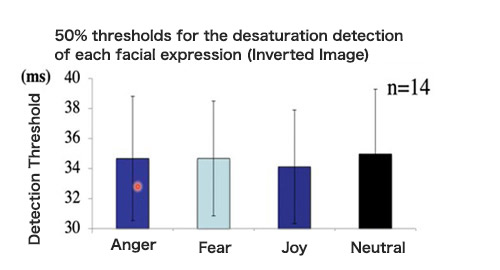

The results from upright images indicate that not only anger and fear, but also positive emotions such as joy increase temporal precision in perception compared to neutral subjects, enabling faster recognition despite the brief duration (Figure 4). Conversely, in the results for inverted images, where facial expressions are challenging to discern, no differences were observed among the four image types (Figure 5).

These results demonstrate that the sensation of ‘thrill’ itself is crucial for time perception rather than factors such as brightness, color, or the pleasantness/unpleasantness of the facial expressions in the image.

Pursuing an environment where people’s cognitive abilities are optimized

During this IAAR seminar, I introduced the process behind the demonstration of ‘Tachypsychia,’ wherein individuals perceive time to slow down when faced with danger for the first time globally. I aim to study further how various emotions influence this phenomenon, exploring whether heightened emotional states lead to additional alteration in time perception.

Moreover, my team is now actively investigating the mental states of intense concentration, commonly referred to as the ‘zone’ or ‘flow state,’ which are often observed in athletes and high-performing individuals. It is believed that emotions, particularly arousal levels, along with intrinsic attention*, accelerate visual information processing and improve temporal precision.

*Endogenous attention refers to the conscious directing of attention to a specific location. In contrast, exogenous attention involves the unconscious automatic attraction to stimuli that appear and disappear unintentionally.

Drawing from the insights gained from these studies, I set my next step to investigate in more detail environments and conditions that optimize human cognitive capabilities. This includes exploring situations where rapid decisions can be made in extremely short periods. I envision collaborating with the fields of science and neuroscience, leveraging cutting-edge technologies like functional MRA (fMRI), one of the most advanced neuroimaging techniques available today, to deepen our understanding of perception and cognition.

Looking to the future, my aim is to spearhead research efforts that contribute to creating a safer society. This involves continuing to advance technologies aimed at drawing attention to traffic warnings and reducing traffic accidents.

Recommend

-

Optimizing End-of-Life Happiness: The Future of Nursing through Technology

2024.05.31

-

Creating a Pandemic-Resilient Society to Tackle Future Invisible Enemies

2022.10.25

-

‘Synergistic Campus Evolution with the Community’ Chiba University Design Research Institute (Part 2): Igniting ‘Cross-fertilization’ for a Revolutionary Vision

2023.12.25