Did you know that not only the seeds of plants are sources of oil, but also their leaves? Here is a researcher who is fascinated by lipid droplets that accumulate drop-by-drop in plants. He is now searching for ways to increase the production of such plant oils, with the aim of helping to solve the world’s food problems.

His name is Associate Professor Takashi Shimada of the Graduate School of Horticulture. Dr. Shimada is aware of the people and environments that have given him so much, and he wants to give back some of what he has received. With a research design that aims to benefit society and his dedication to teaching and developing the youth, he has set his sights high. We asked him about the people he has interacted with and his research style.

Encouraged by parents and classmates

I feel that I have had very good fortune in my life, as I have been blessed with good people around me and good environments. One of the dear memories from my youth is how my family supported me when I sat for the entrance test of the junior high school I hoped to join. I believe that they helped to foster in me, in a natural way, a kind of self-reliance, which enables me to think things through and then act accordingly.

It was in my high school days that I took a particular interest in biology. As I was attracted to paleontology, geology, and other sciences, I chose the Faculty of Science at Kyoto University as the place where I wanted to further my studies. Many of my high school classmates also took the test for Kyoto University, and I was glad we could share study methods and other information. The test was tough, but I believe it was thanks to their help that I was accepted at Kyoto.

During the interview, Dr. Shimada spoke countless words of gratitude.

Encounters with first-class professors taught him researchers’ way of life

When I first entered university, I wanted to do research on animals. However, I learned from practice and training that it didn’t suit me. For example, it was almost impossible for me to dissect a mouse! So, I turned my interest to plants, which I felt might be more enjoyable.

I was working in the lab of Professor Ikuko Nishimura, which was mainly performing research on the proteins stored in plant cells. Since I had a stubborn side, I was the only one who chose fats instead of proteins as my topic

A desire to be different from others and to stand out

Even I think that I have a troublesome personality. However, I feel that it is crucial for a researcher to have qualities and sensibilities that differ considerably from the mainstream and allow one to walk their own path. In the research world, it is meaningless to do the same things as others.

Kyoto University for superior education, and for “academic freedom”

I was deeply impressed by my top-class professors at Kyoto University and their lively way of teaching and instructing.

The first thing that struck me was the abundance of imagination and new ideas. How wonderful it was to see that even after decades of working in the same field, it never became tedious and mundane—they still maintained the ability to generate completely new ideas.

I was also moved by their dedication to teaching. Whenever I visited professors, they always stopped whatever they were doing and focused on me. They never outright denied a student’s opinion, but instead patiently described the points that they felt were scientifically unfounded and showed the basis for their explanations. I never saw any professor reject a student’s ideas with any negative emotions.

There, students could pursue studies with confidence. I learned the importance of an environment where a student can consult a professor if there is difficulty or worry. They taught me what leadership in the laboratory truly means.

Always looking forward to changes in surrounding environments with a positive attitude

A move to the East expands his horizon: he gains new approaches to his research

After my time was up at Kyoto University, I transferred to the laboratory of a professor I knew at the University of Tokyo. Many people from the Kansai region face big hurdles in adapting to a new life in Kanto, but I was the opposite. I couldn’t help but look forward to seeing a new world and meeting new people.

I soon found huge discoveries in conversations with my new seniors at the University of Tokyo. The professors there seem to be of the logical-thinking type. They think things through with thorough reasoning, then create a story to perform experiments for those parts of the story where there is not enough data. It’s like a world where everyone is assembling intricate jigsaw puzzles, piece by piece.

Reacting without confusion to aspects that differed from his prior research practices, Dr. Shimada simply accepted his insufficiencies and improved his skills as a researcher.

The style of the professors was so different from that of those at Kyoto University, where the teachers emphasized new ideas. While I was shocked, I also found things that were lacking in my approaches. It’s no exaggeration to say that this was a turning point in my career as a professional researcher.

In fact, freedom of imagination and intricate logic are the two wheels that ideally drive research. Moving to a new lab allowed me to see both perspectives and gave me a great advantage. I really cannot be grateful enough for these experiences.

To be a researcher who contributes to the world’s future

As a student, I chose fat and oil accumulated in plants as a research theme because it seemed somewhat “different from the crowd.” Since then, I have kept on pursuing this fascinating theme, which is now called “Lipid droplets.” It is a pure sense of wonder that motivates me in this research, as I genuinely want to know “how” and “why” these droplets exist.

My honest desire is to be deeply involved in fundamental research. If I do, however, I may become a kind of “smug” researcher. So, I try to see my role objectively and expand my viewpoints gradually. Then, I can strive for a research design that ensures my research can be extended into contributions to society.

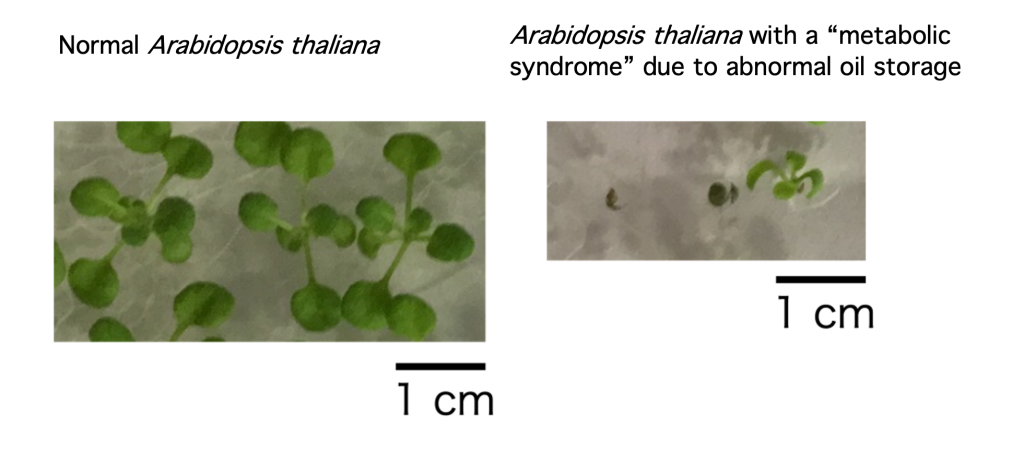

That’s when I came to the global food crisis. Plants accumulate oils mainly in their seeds. At the same time, those seeds are an essential source of human food and animal feed. Thinking about corn or soybeans is probably the easiest way to understand this. These grains began to be traded as a bioethanol source at high prices in the 2000s and beyond, exacerbating global food problems.

So, I thought that maybe oils could be accumulated in leaves, besides seeds. This idea would provide a practical use for the leaves, which are now discarded as trash, meaning the leaves could become a food source without additional competition, as is the case for seeds. I was thrilled with the idea that I could pursue basic research I love and yet, work on practical research that could directly benefit society.

Oils accumulated in plant leaves can be a promising resource for food oils, biofuels, and completely new items, including plant-derived plastics. I am looking for colleagues with flexible and creative ideas who can find solutions to the problems we face. I am also ready to engage in collaborative research with private companies.

In 2019, Dr. Shimada’s article was published in Nature Plants. Then, in 2020, he received the 16th Award for Young Agricultural Researchers from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. The following year, he was awarded the Chiba University Award for Distinguished Researcher 2021. His arduous research labors are flowering and bearing fruit.

It was a great honor to publish in a leading scientific journal and to receive awards. However, I know that these were recognitions of my past research successes. I need to continue my research without resting on my laurels and show the same high-level results in the future. This is what I say to myself to keep me motivated!

Things to focus on in addition to research

I want to educate and train students who can become future leaders. Until now, I have mainly been involved in single-person research, and I always wished I had “another me.” If “another me” joined my research, then I could perform research at twice the speed.

Recently, however, I have found that working with other researchers who think differently from me adds so much more—it broadens my entire worldview to an astonishing degree. Certainly, the research goes a little less quickly, but the extent of its development is like the difference between night and day.

During my days at Kyoto University, I thought I would never be able to do what my great professors constantly did, to stop all they were doing and listen carefully and quietly to their students. Now, however, when my students come to me for discussions, that time leads to benefits for my own research in ways that cannot be obtained otherwise.

I never want to forget the precepts I learned from my former professors: unfettered thinking, elaborate theorizing, and an accepting and positive attitude. I want to be the kind of educator that both students and visitors from private companies and others can visit freely. I want to continue to provide an open and accessible research environment. I will also consult with students about their personal ambitions and give them advice about which research lab is best suited for them. I invite everyone to come over to my lab at the Nishi-Chiba campus. Please have a look!

Recommend

-

Creating a Captivating Play Area for Kids: Inspiring Creativity through Innovative Play Equipment Design

2024.01.17

-

Functioning of Biological Diversity: Lessons from Ecology on the Importance of Minority Perspectives

2023.06.15

-

Affecting behavioral changes through a combination of mind and body: How can we calmly cope with stress in the event of a disaster?

2023.02.27