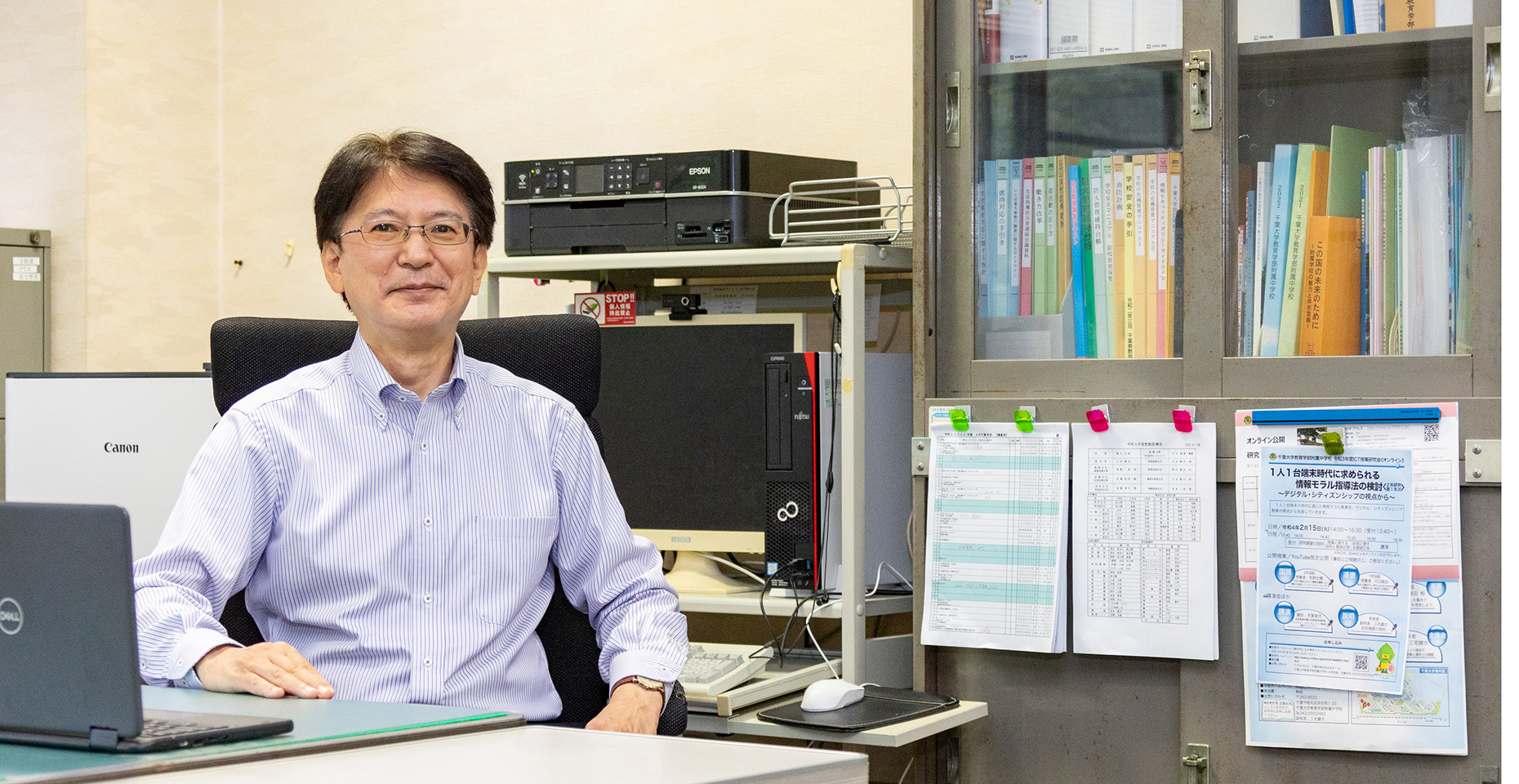

Today in Japan, personal computers and digital tablets are actively used even in elementary schools. Until recently, it was common for parents and teachers to unilaterally restrict, fearing the risks of children using these devices. The emphasis now is on “digital citizenship,” where students think on their own and make their own choices regarding “best behavior.” To understand the rise of information and communications technology (ICT)-based education from its inception to its use in current times, we spoke with Professor Kenji Miyake, Vice-Principal of the Junior High School affiliated with the Faculty of Education, Chiba University. With the complete support and trust of Professor Daisuke Fujikawa, the Principal of the school, Professor Miyake is moving forward with ICT education.

Launching ICT education in the 1990s with the involvement of the Junior High School

Please tell us about the timeline of your involvement in ICT education.

After serving as a teacher in Industrial Arts at a junior high school in Chiba City, I joined the Junior High School affiliated with Chiba University in 1989. In 1992, we finished setting up an environment where each student could use a laptop computer, and I started a programming class. Then in 1994, we began using the internet in our classroom.

So, 1994. That was before Windows 95 came out.

Yes, compared with most schools, we had a considerably early start. I remember showing students the website of the U.S. White House to demonstrate the power of using the internet to browse information from international locations. Yet, the students’ response was less than enthusiastic. What they were really impressed with was the ability to send electronic mail to other students who were not in their vicinity. So, I was struck by the realization that adults and young students can have different interests! A lot of foolishness went back and forth as a result of letting students freely send emails. Hence, I felt that we needed to teach them to use the internet better through our classes. This was when we began to incorporate “information ethics” in our classes.

That said, we never used content filters on the personal computers in our PC room. We wanted to see how the students would use the services in an environment that enabled uninhibited internet use.

How was it when you let students use it without restrictions?

As you can imagine, a variety of problems occurred. We were busy mentoring students and apologizing to those who were victimized. Let me give you a specific example. There was a situation in which some students, using the names of other students, were bad-mouthing others in their communications. The problem escalated to the point where students began to write inappropriate messages on internet bulletin boards. The students were unaware that their log marks were on these messages, so they thought that they could post anything anonymously.

Now, we would never have been aware of these problems if we had started using content filters. Thanks to our experiences, we were able to create a lot of educational materials on information ethics, and ways to properly use the internet. We had a mission, one could say, to serve as a “model school” for other schools which sought to teach their students about these issues. We were then able to shift our emphasis to ICT education.

Actually, the term “ICT education” did not come into use until 2005. Previously, we called it “information education” at our Junior High School and were already engaged in issues that would become prominent 5 or 10 years later.

The coronavirus pandemic spurs on the GIGA School Plan

Recently, we have been hearing about the term—GIGA School Plan. What kind of measures are they?

The GIGA School Plan aims to equip schools with super-high-speed communications networks, and to distribute a digital terminal to each and every student at elementary, junior high, and special-needs support schools in Japan. This program, thus, supports the establishment of an environment where ICT devices can be used actively within schools. GIGA is an abbreviation of “Global and Innovation Gateway for All.” I consider it to imply a gateway to international society and innovative technologies for all young students.

In an OECD survey of academic abilities in 2018, Japan ranked last in ICT usage in classrooms. The Government launched the GIGA School Plan via the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to address this serious issue. Initially, the goal was to address it by 2023, but the coronavirus pandemic spurred on this initiative, since we wanted to ensure that students could continue their studies at home while schools were closed. So, 2021 became the target year.

Certainly, the coronavirus epidemic resulted in a dramatic acceleration of ICT usage. Are there any negative consequences of that?

In general, the response has been positive. However, in households with limited smartphone use, school-provided handsets allowed children to use them for extended periods of time, which worried several parents. Looking back, however, since the introduction of computer game devices at home in the 1980s, such a conflict has existed between children who want unlimited use, and parents who want to regulate usage.

Certainly, parents used to have the option of taking away their children’s gaming devices and smartphones. However, this was no longer an option when children started using these devices to do their schoolwork! The key, then, is in children themselves gaining an understanding of why they should place limits on their own use of these devices.

Digital citizenship is required for personal autonomy in our contemporary era

So, children themselves should think about how and why they use their ICT devices. That sounds ideal, but there seem to be a lot of hurdles to overcome first.

Before students had their own digital terminals, cell phones, and smartphones were widely and rapidly disseminated in society. The speed was so fast that we could not provide “bottom-up” education on information ethics. This implies that students only received the “top-down” guidance where schoolteachers and external instructors gave them warnings and stern proclamations. Now, such warnings may have an immediate effect, but certainly do not frequently result in long-term behavioral changes. And while teaching methods—which involve checks to ensure that prohibitions are followed, and risks are avoided—have a certain impact, they are never enough to grant young people the ability to make their own decisions and become personally responsible within our information-driven society.

In this case, we turn to the concept of “digital citizenship” touted in Europe and North America.

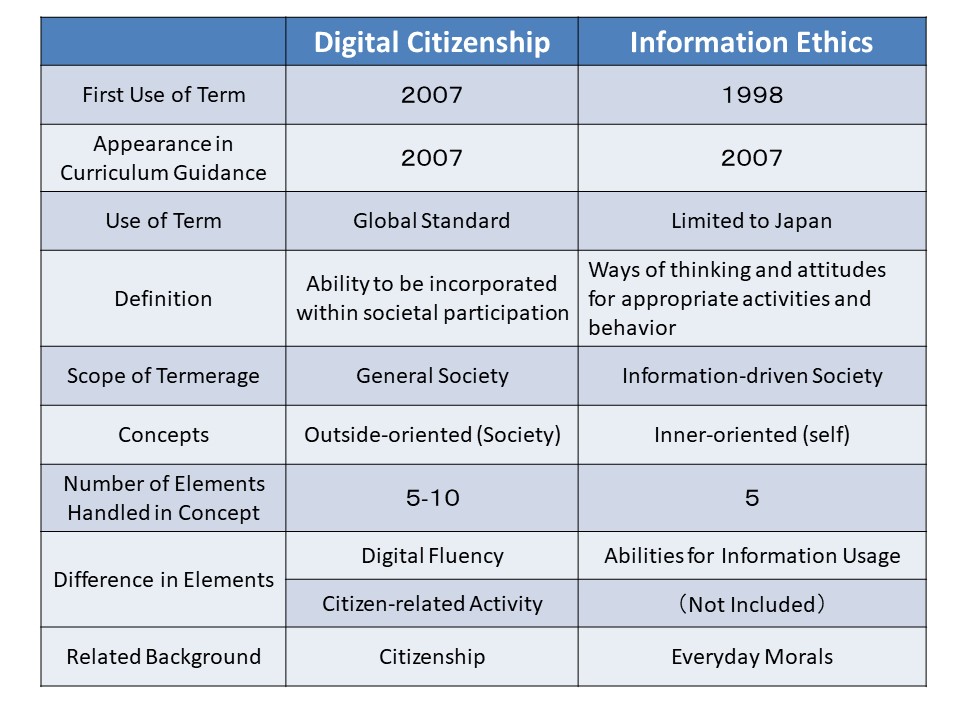

Are there any differences between “information ethics” and “digital citizenship?”

Conceptually, these concepts have major differences in their approaches to information technology. “Information ethics” is more “Inner-oriented” education that focuses on the negative aspects of a smartphone and personal computer usage and encourages introspection about one’s own attitudes and behaviors.

“Digital citizenship” is instead “outside-oriented” education. It looks at the broad picture of our modern society, where digital information is abundant and present everywhere. It teaches proactive consideration about the use of digital media, by people aware of their own citizenship in contemporary societies.

The iPhone appeared on the market in 2007. So, anyone aged 15 years or younger is quite familiar with palm- and hand-sized digital terminals, which are mainstream devices used today. It might even seem unnatural for these people to accept that there is a divide between digital and analog, and between the internet and “real life.”

Yes, we continue to teach the key elements of conventional “information ethics” education, while incorporating these ideas in the deeper and broader digital citizenship education in which we are currently engaged.

What kind of classes are used for digital citizenship education?

We are of the opinion that digital citizenship is not only taught in the classroom but includes skills that are cultivated in every educational and related activity performed at or by the school. This includes school classes, school administration, school club activities, and others. As an example from the classroom, in our Japanese language classes, we cultivate information usage capabilities and critical-thinking skills. In our morals (civics) classes, we use digital citizenship while holding discussions and encourage active student participation in society.

Here is an example of a topic covered in our social studies curriculum, where we discuss the “right to be forgotten” as a new human right that has gained attention in recent years.

This curriculum draws on real court cases where individuals seek to have unfavorable past information posted on the internet removed. We discuss the importance of such cases from overseas. In fact, in Japan, a similar case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that contents of “high importance to the society” cannot be deleted. We note, however, that there is no final answer or solution to issues like these. What is deemed “high importance to a society” may change from one era to another. And not only the general society—different individuals may also have different interpretations. The so-called “right to be forgotten” is “the right to privacy.” This contrasts with “the right to know.” Teachers and students look at and discuss each case through these widely different viewpoints.

To foster the next generations for the future society

We are moving toward a world where there are no distinct “correct” answers. To handle the various issues that they will come across in their lifetimes, students need to consider how they think about each issue and what their response should be. They need to be able to actively put into play their creative abilities and their abilities to come up with autonomous and well-grounded responses.

As for ICT, students need to be able to think for themselves about the best ways in which they can utilize available technologies and resources and enhance their abilities to find optimal solutions whenever and wherever necessary. Through digital citizenship education, children will gain the foundational skills they need to think for themselves, and use their devices freely. Such an education will help future generations to live and work effectively in the present and future society. That is my core idea.

Series

Paving the Way for the Future of Children

Efforts to support the healthy growth of children are crucial. Our researchers confront the social issues surrounding modern children to protect “Children’s Present and Future.”

-

#1

2023.02.15

Children-centered support and school operations: On the occasion of the founding of the Children and Families Agency

-

#2

2023.03.10

What is “Digital Citizenship” Education that lives in a future society?

-

#3

2023.04.19

“Journey of the Brave,” a new cognitive behavioral therapy program: a solution for children’s anxiety

-

#4

2023.05.26

Examining Social Injustice of Modern Society through “Child Poverty”: Creating a Society Where Every Parent is Respected, and Every Child Thrives

-

#5

2023.06.16

Fostering Inclusive Education for the Gifted and All: Unlocking Northern European Insights for Special Needs Learners

Recommend

-

The joy of revealing the unknown: The challenge of solving the mystery of the Sun

2022.09.28

-

Decoding the Secrets in Art: The Art and Legacy of Early Modern European Female Painters

2024.07.24

-

Designing a world-class climate-resistant fruit!~Developing “Designed Grapes” for Custom-Made Wine to Commemorate Special Occasions

2022.11.07