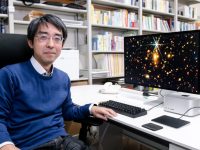

“Pests are words from a human point of view.” When he said it, I realized the hidden arrogance of human beings. Professor Masashi Nomura, from the Graduate School of Horticulture, possesses a deep love for insects, favoring live observation over specimen collection. He even conducts annual insect classes for children. Together, we are endeavoring to discover an environment where humans and insects can coexist harmoniously by harnessing the ecological potential of these creatures.

Insects as ‘close friends’ during the childhood days

―It seems you’ve been passionate about insects since childhood. Could you share some of your childhood memories involving these creatures?

For as long as I can remember, insects have been my ‘close friends.’ My parents, too, were very accommodating; they maintained a container with over 30 praying mantises nestled amidst plastic containers for strawberries, and upon returning from school, I’d gather grasshoppers to feed them. Even today, I only collect specimens when absolutely necessary for my research. Observing live insects is infinitely more enjoyable than preserving dead specimens.

Upon joining Chiba University’s Graduate School of Horticulture, I began contemplating the role of insects in horticulture. In agriculture dominated by humans, crop-eating insects are typically labeled as pests. However, calling them ‘pests’ solely based on their crop damage feels overly simplistic and disheartening. Instead of resorting to potent pesticides, my research revolves around establishing a more harmonious balance between insects, people, and crops while actively managing the environment.

Skillful survival strategies that adeptly detect various signals like seasons and time

Insects exhibit seasonal patterns of activity. Swallowtail butterflies lay their eggs on the new shoots of citrus plants such as mandarin oranges and Japanese peppers in the spring. The larvae hatch from these eggs and thrive by consuming the leaves. Cicadas, on the other hand, spend an extended period underground, emerging during the summer evenings and nights to hatch and complete their life cycle.

―Why do insects synchronize their activities with the seasons?

To illustrate this with the previous example, the fresh shoots that serve as the primary food source for Swallowtail butterfly larvae appear in spring. If the larvae were to emerge and lay eggs when there are no new shoots, they would inevitably starve due to the lack of sustenance. Cicadas, as adults, have a relatively short lifespan, typically lasting no more than a month, during which they must reproduce. Therefore, aligning their emergence timing is believed to increase their mating success rate. Ensuring the continuation of their species in this manner underscores the utmost importance of synchronizing their life cycles with the seasons.

―How do insects perceive the seasons and time?

Insects, much like us, possess biological clocks that determine the length of day and night. For example, overwintering species ‘activate’ dormancy as the nights get progressively longer. If this were solely a temperature sensor instead of an internal clock tracking day-night cycles, it would easily malfunction during unseasonably hot or cold spells. By attuning themselves to the consistent rhythms of day and night, insects can harmonize their activities with the calendar.

Recent research has shown that insects not only monitor the duration of day and night but also sense various chemicals. For instance, there is speculation that they adeptly navigate their environment through ‘communication’ with other insects and plants, even distinguishing between the scents of the plants they feed on and those of their natural enemies.

Effects of climate change and pesticides on insects

―Climate change, such as global warming, is a widely discussed topic. Does it also have an impact on insects?

The ‘dormancy switch ON’ is triggered by the length of the night, while the ‘wake-up switch ON’ requires a certain period of low temperatures. Similarly, cherry blossoms also require a cold winter period: Flower buds that have entered dormancy are exposed to low temperatures for a certain period of time in winter and awaken from dormancy, leading to the blooming of flowers in spring.

Insects seem to remain in a prolonged state of gradual awakening when adequate cooling is lacking due to a mild winter. As mentioned earlier, this can result in issues such as difficulty finding food or reduced mating opportunities. We must continue to closely monitor the impact of global warming on insects.

―So you can’t underestimate the impact of climate change

In recent years, with the increase in large typhoons and the persistence of seasonal rain fronts, there has been a rise in the number of species brought from overseas. Among these insects, some exhibit strong pesticide resistance. It is possible they developed this resistance due to the continuous use of the same pesticides. Even if new and effective pesticides are developed, resistance is likely to emerge eventually.

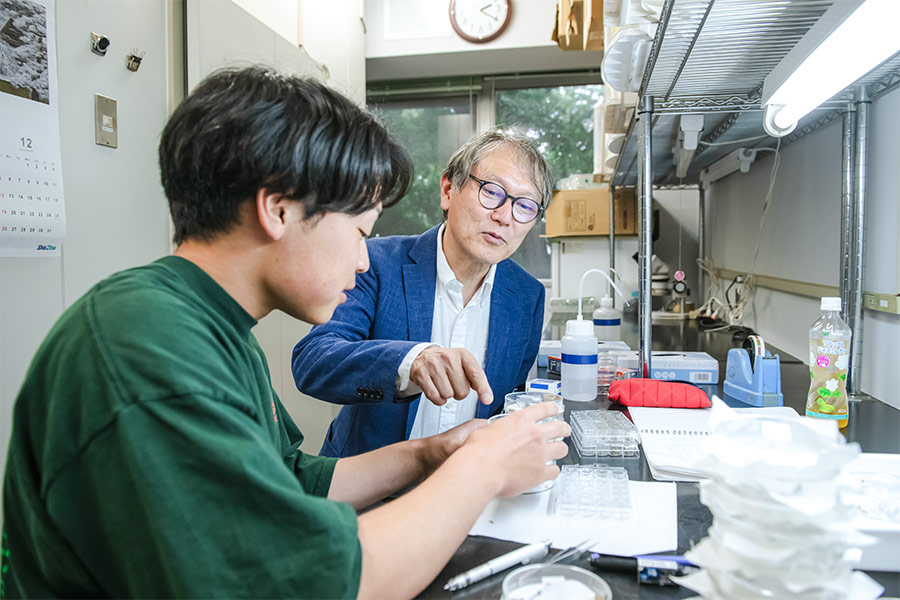

In our laboratory, we have been commissioned by the Japan Plant Protection Association to conduct ‘practical tests of new pesticides.’ These tests aim to verify whether newly developed pesticides are effective as intended on real farms. We have been in operation for over 70 years since its establishment in 1951. This testing also underscores that pesticides should not be applied indiscriminately, but rather should be used properly based on the specific species to demonstrate their effectiveness accurately.

Insect control using light

I heard that you think there are no ‘naturally born pests’

The reason pests appear is due to the advancement of agriculture, where large quantities of the same crop are produced in one area. There is no other explanation for why cabbage butterflies, which feed on cabbage, thrive in cabbage fields―it’s simply because they find their food source there. Calling them ‘pests’ seems a bit one-sided, given that their population explosion is a result of human activity.

That being said, we still need to protect our crops. Using pesticides is necessary to prevent serious damage. However, I’m also researching methods to deter insects without relying on pesticides. One of these methods involves utilizing light as a control technology.

I thought insects were attracted to light

While it’s true that they exhibit a ‘positive’ phototaxis, they also have a tendency to avoid ‘yellow light.’ Have you ever seen greenhouses and fields lit up with yellow LED lights at night? Yellow light not only repels moths, such as noctuids*, but also reduces the activity of noctuids already in the field. It is believed that the yellow wavelength tricks their compound eyes into perceiving it as daylight, thereby suppressing the nighttime activity of these nocturnal moths.

However, nighttime lighting can delay flowering in short-day plants* like chrysanthemums. After searching for lighting conditions that effectively deter noctuids without affecting autumn chrysanthemums, we found that a 1:4 on-to-off lighting ratio strikes the best balance.

* Noctuids: Moths that damage many horticultural crops

*Short-day plants: Plants that form flower buds when daylight hours become shorter

In addition, unlike humans, insects can see ultraviolet light. When insect-pollinated flowers, such as cherry blossoms, mandarin oranges, and tomatoes, use ultraviolet light to guide insects. They absorb it in the center, appearing dark, while reflecting it at the periphery, appearing bright. It’s like the flowers saying, “There’s nectar here!” While LED lighting in plant factories is thriving, it mainly utilizes red and blue visible light, lacking ultraviolet light. When considering future pollination needs, I believe incorporating UV rays may also be necessary.

The fascination of the world seen through insect ecology

Finally, please share your message and your future goals with students who have a passion for insects and parents with children

Even when observing the ecology of small insects, it raises questions. Simple inquiries like “Why aren’t they eating today?” or “Why do butterflies have different patterns on their wings?” are excellent starting points. Read your textbook critically, asking, “Is this really true?” and observe further. Please cherish the thoughts you gather through this process, as new research often emerges from them.

When you think of the word ‘insect,’ you probably imagine splendid species such as beetles and swallowtail butterflies. However, many insects are small and live inconspicuously. Participating in our annual insect classes is a great way for parents and children to cultivate their ‘insect observation skills.’

In the modern city, the opportunities to get close to insects are dwindling. More and more people think that an environment without insects is cleaner and preferable. However, from a macro perspective, insects serve as the foundation of ecosystems, providing food for birds and other animals. In an environment without insects, somewhere within the ecosystem, things have gone away. Looking at insects as vital companions of our planet, we aim to create a society where harmonious coexistence is possible.