Hironobu Aoki, an assistant professor at Chiba University’s Design Research Institute (dri), has been engaged in unconventional design research centered around historic temples in Chiba Prefecture since his student days, predating the establishment of dri. His focus lies in the ‘Utilization of 3D data,’ leveraging digital modeling equipment extensively in his research endeavor. In our conversation, we asked how ‘Advanced Technology’ augments the scope of design and its connection with the ‘Local Community.

Obtaining 3D data for ‘Community Design’

Upon learning about your research involving ‘acquiring three-dimensional data on Buddhist statue shapes,’ I initially thought your study field was akin to art history.

I not only digitize Buddhist statues but also preserve everyday objects, which can be found throughout Japan’s diverse regions since ancient times, as digital data. Rather than mere collection and storage, my research endeavors to leverage this data for community revitalization and beyond.

Did you know that there are approximately 3,000 temples in Chiba Prefecture? Among them, Komatsuji Temple in Minamiboso City, is renowned as a ‘Treasure trove of ancient Buddhas,’ housing a vast collection of precious Buddhist statues. Some of these statues date back over 900 years, originating from the early Heian period (794-1185). I have taken 3D scans of these Buddha statues and created exact replicas. With these replicas, anyone can experience the statues from 360-degree angles, allowing for a deeper appreciation and serving one form of ‘heritage utilization.’

Recognizing the importance of tactile interaction with these statues, I have also exhibited replicas of the hands of each Buddha statue in the main hall of a temple. Fortunately, this initiative has attracted numerous visitors, sparking interest in the distinction between merely observing and physically engaging with Buddhist statues. It has provided a unique opportunity for visitors to deepen their understanding and emotional connection to these ancient relics.

Instead of solely researching culturally and historically significant assets, my research focuses on identifying the “resources” within a region and strategizing ways to integrate them into community revitalization efforts.

Your activities sound different from what is typically called a ‘design’ study

Design is often perceived as solely considering the shape and color of an object. While that is indeed a facet of design, considering the condition of a region and its society is also a form of design. However, rather than unilaterally imposing proposals like ‘this region possesses these resources, so we should implement this solution,” it is crucial to engage in collaborative thinking with local stakeholders and everyone involved. I place great value on this collaborative approach. In essence, for me, ‘design’ can be described as a social movement aimed at rediscovering the unique attributes of a region and fostering discourse throughout the community.

Creating a ‘3D replica’ is not a goal

――Chiba Prefecture has always been your research field. With the establishment of dri, you have forged connections with Sumida Ward. Have you initiated any new research projects in Sumida Ward as well?

Yes. Indeed, I am currently collecting 3D data of stone monuments and other stone structures in Sumida Ward. I’ve heard that there are many stone monuments in the area, but due to constant exposure to wind and rain, they risk crumbling and being lost if left unattended.

I, therefore, took 3D data of a marine disaster monument shaped like a sailing ship in 2021. I aim to promote universal design, ensuring ease of use for individuals regardless of age, gender, nationality, culture, ability, or situation. As part of this effort, I’m working on creating full-size replicas using 3D printers to cater to people with visual disability.

Touching the replica allows you to feel its shape and even the kanji, Chinese characters, carved into the stone.

Yes, indeed. However, as some people with visual disabilities might not be familiar with kanji characters, it is important to consider the accessibility aspect further. Simply relying on tactile sensation is not sufficient. To truly help people understand the content and shape of the carved characters, providing context on the origin of kanji is essential. Moreover, utilizing audio aids would significantly enhance their comprehension. Mere replication using a 3D printer fails to capture the essence and weight of the original.

Understanding the ‘intended message’ behind the stonework is crucial for presenting the object according to its purpose. This requires thoughtful consideration and innovation, both of which are integral aspects of my research into effective ‘utilization.’ As such, I customize tools and methods to suit the specific purpose at hand. While possessing 3D data is valuable, it does not mandate strict adherence to a 3D printing approach.

Complete range of digital modeling equipment at dri

At dri, you have access to a diverse array of options with a wide range of digital printing equipment

The environment at dri is exceptional. Alongside our 3D printers and laser cutters, one recent addition that brought me great joy personally is the arrival of a large 3D cutting machine. This machine enables us to work with natural materials like wood, facilitating the crafting of intricate curves and shapes with ease.

What do you prioritize when instructing your students on how to use these devices?

Instead of simply assigning tasks like “make this,” I urge students to determine their own projects. I offer guidance by suggesting suitable machines or methods based on their ideas and fostering discussion.

Rather than imposing a rigid plan from the start, I encourage students to embrace trial and error as a natural part of the learning process. While securing safety, I advocate for hands-on experimentation in design. If their initial attempts fail, I prompt students to reflect on why and iterate accordingly. The insights gained from this interactive process are invaluable.

Skills in utilizing 3D data to create new objects with digital modeling equipment seem valuable across various fields.

That’s right. I sometimes invite my students to my project, saying, “Even if you’re not particularly interested in local resources or community revitalization, wouldn’t you like to explore this technology’s potential for diverse applications in the future?”

Local resources are not always easily observable; they are intricately woven into the natural landscape. Thus, simply looking around may not reveal them. However, through concrete actions like collecting 3D data, engaging in hands-on exploration, and attempting to create objects, clarity emerges. At dri, what sets us apart is the opportunity not only to ‘observe’ and ‘think,’ but also ‘try firsthand.’

Prompting the utilization of local resources from Chiba and Sumida

Are there any international students in your laboratory?

Yes. Many are from Asian countries. Appreciating this connection, I have started researching historical objects in students’ respective countries. Similar to Japan, many of these nations possess abundant ‘cultural resources’ that are not formally preserved or exhibited as important cultural properties that hold deep cultural significance in people’s lives. Therefore, I am documenting them as data.

For example, in certain regions of Taiwan, there exists a tradition of papermaking using bamboo as a material. During my visit, I found distinctive tools specific to that area. I took 3D data of large stone rings utilized for crushing bamboo. In the future, I aspire to contribute to the preservation and revitalization of local cultures overseas by collaborating with local practitioners and researchers.

There are countless heritages waiting to be documented across the world

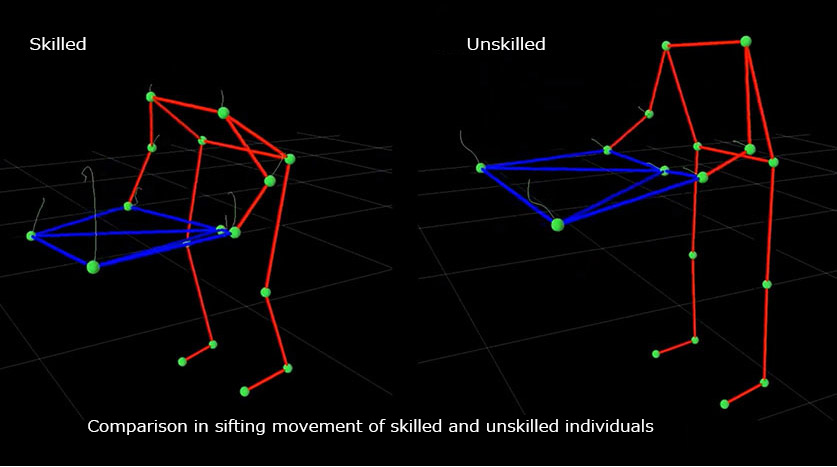

I firmly believe that each region has its own unique cultural assets, many of which may not be ‘visible.’ Take, for example, the case of Sosa City in Chiba Prefecture, where a traditional tool called the ‘Mi’ is created and used to sift grains like rice and shake off the dust, a practice passed down through generations. While physical tools themselves are often preserved and studied, the dynamic ‘act’ of wielding the ‘Mi’ is challenging to capture and preserve as a historical record.

Therefore, in collaboration with another laboratory, we undertook the task of recording the intricate motions involved in using the ‘Mi’ through motion capture technology. This endeavor revealed distinct differences in technique between skilled and unskilled individuals, offering valuable insights that could facilitate regional comparisons.

The widespread adoption of motion capture technology represents a significant advancement. In recent years, acquiring high-quality 3D data for objects has become increasingly accessible, with even smartphones capable of fulfilling this purpose. This accessibility signifies a promising development, democratizing the tools necessary to utilize local resources for everyone’s benefit.

My affiliation with Chiba University dates back to my student years, and my deep affection for Chiba Prefecture drives my desire to actively explore and utilize its local resources. While my relationships and efforts have begun to extend into areas like Sumida Ward in Tokyo, it’s evident that I can’t single-handedly cover every region. The ideal scenario is individuals from various parts of Japan contributing to this project, each saying, ‘I take care of my area!’

Series

The Power of Design

Meet our dynamic faculty members at the Design Research Institute (dri), a hub for designing future lifestyles located at Chiba University’s Sumida Satellite Campus

-

#1

2023.12.21

‘Synergistic Campus Evolution with the Community’ Chiba University Design Research Institute (Part 1): The Entire Campus as a ‘Design Experiment Space’

-

#2

2023.12.25

‘Synergistic Campus Evolution with the Community’ Chiba University Design Research Institute (Part 2): Igniting ‘Cross-fertilization’ for a Revolutionary Vision

-

#3

2024.01.17

Creating a Captivating Play Area for Kids: Inspiring Creativity through Innovative Play Equipment Design

-

#4

2024.01.26

Designing a Comfortable Living: A Kampo Clinic that Simulates the Five Senses

-

#5

2024.02.09

Creating Cities of Coexistence: Transitional Landscapes with the Tapestry of Diverse Lives

-

#6

2024.02.26

Designing Mobility: A Gentle Force in Linking People and Society

-

#7

2024.03.29

Touchable Buddha Project: Bridging Heritage and 3D Technology for Community Revitalization through Design

Recommend

-

Non-Injectable Mucosal Vaccines Providing Safe and Less Stressful Immunization

2022.07.26

-

Decoding Epigenome Modification Errors: Exploring Immunological Mechanisms by a Two-way Player in Biology and Data Science

2024.06.27

-

The Global Goal of Carbon Neutrality by 2050 (Part 2): A decarbonized society from a local perspective

2023.07.14