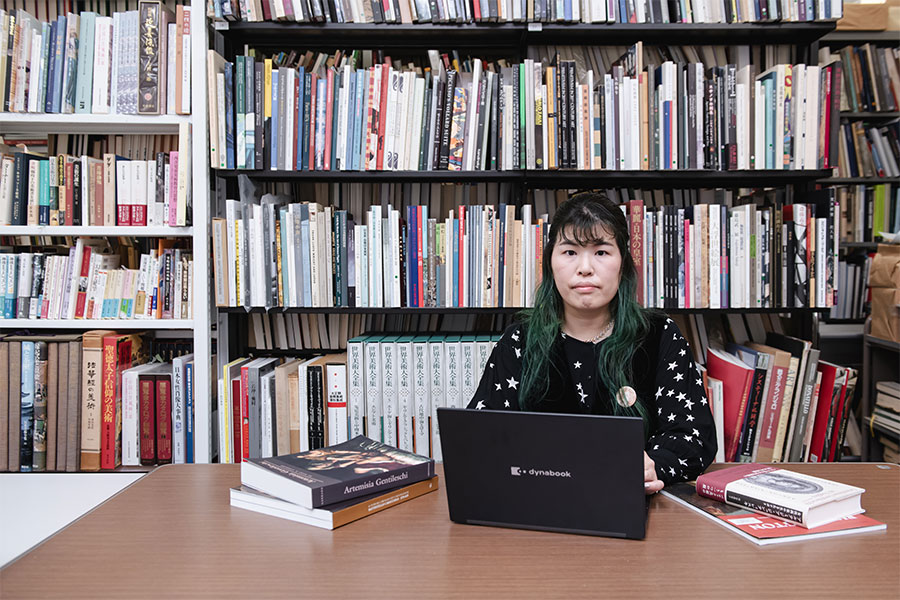

Unraveling the secrets of paintings is like deciphering a code that reveals hidden meanings one by one. We spoke with Makiko Kawai, an art historian and assistant professor at the Graduate School of Humanities at Chiba University, who is gaining attention for her research on early modern European female painters. Her work sheds new light on the allure of these paintings and the surprising aspects of the artists themselves. After reading this interview, you might view these paintings from a completely different perspective.

What is research to ‘interpret’ paintings?

―You are conducting research related to art, but your approach seems different from that of an artist.

I specialize in art history, which involves analyzing and interpreting visual images like paintings and sculptures from a historical perspective. Initially, I was more interested in preserving cultural heritage rather than creating art myself. I chose this path after realizing that there are many ways to be involved in art without being an artist myself. What’s fascinating about art history is its wide scope—it encompasses various disciplines such as history, religion, and sociology.

―What do you find interesting or difficult about painting?

There is a profound satisfaction in deciphering the meaning and content of a painting that is not explicitly spelled out in words. In Western painting, there is a rich tradition of expression on the canvas. Therefore, once you understand those conventions, hidden meanings start to emerge.

However, this fascination also presents its challenges. While it’s relatively straightforward to extract meaning and dates from written information such as letters, interpreting images often involves navigating multiple possibilities. This makes arriving at the correct interpretation a daunting task.

Painters who promoted themselves with self-portraits –Iconography and Portraiture

―Please provide us with further insights into the conventions of presentation in Western painting.

These rules were developed to convey the contents of the Bible and mythology using only pictures (images) and no text. For example, a book may symbolize culture, while a dog might represent fidelity between husband and wife. In early modern Europe, these symbols were combined to create works with complex allegories. One approach to understanding these allegories is ‘Iconography.’ Although it is often considered the initial hurdle to accessing early modern art, with some knowledge of rules, you can uncover the profound meanings contained within, leading to a dramatic shift in perception of a painting. Recently, there has been a significant increase in the availability of manuals on iconography, indicating a growing interest in the subject. The groundwork laid by Professor Midori Wakakuwa* and other researchers is now bearing fruit.

*Midori Wakakuwa: Professor emeritus at Chiba University, art historian, and pioneer in Japan who left many achievements in image research and gender culture research. Passed away in 2007 at the age of 71.

―I would like to learn more about iconography.

Painters adeptly employed symbols and iconography for self-promotion. When one thinks of a ‘painter,’ many might envision a figure holding a palette and paintbrush in front of a canvas, as depicted in the image on the right.

In fact, there are also more elaborate self-portraits, as seen in the picture below. The artist subtly conveys her social status and level of education by portraying herself playing a musical instrument accompanied by her lady attendant. Additionally, she proudly showcases her identity as a painter by positioning her easel in the background. These ‘glamorous’ self-portraits were often sent to their patrons.

―I didn’t know self-portraits were used for marketing! It’s like a celebrity photo these days.

They are tougher than you can imagine, aren’t they? Furthermore, in early modern Europe, portraits of female painters held another significance. They were expected to be ‘beautiful paintings depicting a woman.’ For example, in the ‘Self-portrait’ by Sofonisba Sanguissola housed in Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, the word ‘Virgo (maiden)’ can be read in the small book she holds. This implies that female painters at the time were expected to be educated, modest, thoughtful, chaste, and beautiful. To be successful, a female painter needed not only talent but also to embody the ideal image of a woman desired by society.

Unconventional female painter “Artemisia Gentileschi”

―Female painters of that era were not only expected to excel in their art but also to adhere to the standards of ‘the ideal woman.’

Artemisia Gentileschi was a painter who made a significant impact. Born into a family of painters, she showed remarkable talent from an early age and was trained by her father. Tragically, at the age of 17, she was sexually assaulted by a tutor. This dramatic chapter in the life of a young and talented woman who overcame such a painful experience garnered much attention. She became an icon in feminist art history, a kind of ‘mythologized figure’ whose story resonated deeply.

Despite these challenges, she achieved extraordinary success for her time, becoming the first woman admitted to the Florence Academy of Fine Arts. Her membership in this prestigious institution underscored her exceptional skill and success as a painter, a rarity for women of her era.

―What made you choose Artemisia Gentileschi as your research subject?

As an undergraduate, I encountered Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting ‘Judith Beheading Holofernes’ (below) and was stuck by its dramatic intensity. My curiosity led me to search for more information, and I discovered that while gender studies and research on Artemisia are advancing in Europe and the United States, there is a notable lack of Japanese documentation. Determined to understand Artemisia Gentileschi as closely to her original form as possible, I focused particularly on the latter half of her life, which remains largely unexplored. Since then, my research has been driven by a desire to uncover and appreciate the true essence of Artemisia Gentileschi.

‘Judith Beheading Holofernes’ (Uffizi Gallery): illustrating a dramatic story from the Book of Judith. When the city of Bethlia, Judith’s home, was besieged by the general Holofernes, she skillfully wormed her way into the enemy camp with her maid. Taking advantage of Holofernes’ drunken state, she beheaded him with his own sword, saving her city. Some believe that Artemisia Gentileschi used her paintings to exact revenge for her own experience of sexual assault.

―What kind of person was she?

She had a keen sense of perception, and, though born in Rome, she pursued work in Florence, Venice, and London―wherever her artistic style was appreciated. She eventually established a workshop in Naples, enjoying great success well in her 60s. In Florence, she served the Medici family, but never rested on her laurels. Instead, she constantly maintained a diverse clientele, ranging from private collectors to churches, skillfully managing risk and taking on any job that came her way.

-Her marketing sense is amazing.

That was the secret to her success. When ‘nudes painted by women’ became popular, she painted numerous female nudes to meet the demands of collectors. She also had a sharp awareness of payment. Even though prices in Naples were lower than in Rome, there is a record of her insisting on Roman rates, declaring, “I am a Roman, and therefore I shall act always in the Roman manner.” (from Mary D. Garrard’ Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art’ Princeton Univ Press 1989)

Re-positioning early modern female painters in history

-Please tell us about your future research prospects.

In recent years, there has been significant progress in researching female artists from the 16th and 17th centuries. My goal is to expand this research to include contemporaries of Artemisia Gentileschi. Currently, I am translating the biographies of Arcangela Palladini and Giovanna Garzoni.

Art historian Griselda Pollock once said, “They were not forgotten, but actively excluded” (Bijutsu Techo, August 2021 issue). The foundations of today’s art history were established in male-dominated societies from the 19th century onwards. To truly advance the field of art history, it is essential to re-position and recognize the neglected female artists of the early modern period.

-Could you send a message to those interested in studying art history?

Art history can be a time-consuming subject, as it requires learning new languages and understanding various social contexts. However, for someone like me, who is naturally a bit of a recluse and rarely goes out unless necessary, I find it so fascinating that I want to study abroad in Italy. I encourage you to take the plunge and try new challenges. I’m sure the world will open up for you.

● ● Off Topic ● ●

Do you have any recommended art museums?

The National Museum of Western Art (Ueno, Tokyo) not only has a wonderful collection of works but also no fixed viewing itinerary, allowing you to see them as you like. You can return to your favorite pieces as many times as you want, and it’s fun to compare artworks and find commonalities in your own way.

To be honest, I don’t know how to appreciate art.

Why not think about who commissioned the painting? Was it ordered by aristocrats to showcase their authority and status, or by the church to convey its doctrines? There are some strange paintings out there. Don’t you find yourself wondering, “Wow, who on earth wanted this picture?” Let your imagination run wild―it’s fun and makes the experience more engaging.

Recommend

-

Decoding Epigenome Modification Errors: Exploring Immunological Mechanisms by a Two-way Player in Biology and Data Science

2024.06.27

-

The Taming of a ‘Wild Horse’ Carbene!: Driving Drug Discovery through Low-energy Pharmaceutical Synthesis

2025.11.26

-

Unraveling the Mysteries of the Feline Mind: Insights from Animal Psychology

2023.05.01