The term ‘ELSI,’ which stands for Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications, has rapidly gained traction in the research community over the past few years. This field examines the ethical, legal, and social aspects of science and technology. However, ELSI remains relatively unfamiliar outside of universities and research institutes. So, is it truly a new field of research? To explore this question, we spoke with Professor Tatsuhiro Kamisato of the Graduate School of Global and Transdisciplinary Studies, who specializes in the history of science, Science, Technology and Society (STS), and risk theory. He shared insights into the origins of ELSI, the next stage known as Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), his journey into this field, and his aspiration for the future.

ELSI is a system that brings together expertise for the benefit of society

What is ELSI?

Science and technology, like smartphones, can offer significant advantages but also pose risks, such as nuclear accidents. These advancements can thus have both positive and negative impacts. ELSI refers to research and initiatives aimed at ensuring that emerging scientific and technological developments are beneficial to society.

To mitigate potential negative impacts, we need not only progress in science and engineering, but also insights from various disciplines within the social sciences and humanities. These include sociology, history, law, economics, ethics, and cultural anthropology. In this sense, ELSI serves as a system that mobilizes all the knowledge we possess to promote the responsible development and application of new technologies.

So, ELSI is more of a system or framework than a research field in itself?

The movement to consider the societal impact of science and technology began to spread in Europe and the United States in the latter half of the 20th century, continuing to this day under the name of STS. However, the term ELSI was first introduced in the U.S. in 1988, with the launch of the Human Genome Project.*

*An international collaborative research project aimed to decode the entire human genome, was initiated in 1991 with a budget of $ 3 billion.

James Watson*, a leading figure in the life sciences and the leader of the Human Genome Project, proposed that 3% of the project’s total budget should be allocated to research on the ELSI of the genome project. This marked the beginning of a system in the U.S. and Europe where a portion of the research budget for projects expected to have a significant social impact is pre-allocated to research in social sciences and humanities.

*American molecular biologist who, along with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the molecular structure of DNA.

In the 2010s, the concept of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI)’ emerged, primarily in Europe, as an evolution beyond ELSI.

RRI involves envisioning the ideal future of society, identifying ELSI-related issues, and proactively reflecting societal needs in the direction of research. The goal is to guide research and innovation with the aim of shaping that ideal society. While ELSI focuses on regulating and mitigating the negative effects of scientific and technological advancements, RRI emphasizes a more proactive, positive approach―ensuring that science and technology are developed in a way that benefits society.

So, are ELSI and RRI discussions centered around STS expertise?

Not exclusively. Researchers from various fields participate in these discussions. Since STS studies are inherently interdisciplinary, they serve as a ‘forum’ where experts from diverse disciplines come to gather to explore the relationship between society, science, and technology. In that sense, the role of STS experts in ELSI discussions is often to connect and coordinate the various specialized fields involved.

With a background in life science and a focus on the history of science

Does that mean your area of expertise isn’t ELSI or STS?

My original field of study is the history of science. My involvement with ELSI comes in two ways: one is studying the historical background and evolution of ELSI and RRI from a history of science perspective, and the other is examining the societal aspects of specific scientific and technological issues, which ultimately takes on an ELSI-related dimension.

An example of the latter would be my research on the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) or ‘mad cow disease’ problem that emerged in Japan in 2001. During my undergraduate years, I studied early bioinformatics at the Faculty of Engineering, which gave me some familiarity with the life sciences. This has led me to focus on the social risks that arise when life is treated industrially. At the time, I wasn’t consciously thinking about ELSI, but looking back, I realize that the research was aligned with ELSI principles.

So, you transitioned from being a science researcher to a humanities researcher.

Yes, after completing my undergraduate degree, I initially worked at the former Science and Technology Agency. However, I soon realized that government work wasn’t the right fit for me, so I returned to university to pursue a doctoral degree in the history of science. Although it involved science, the focus was on history, making it very much a humanities discipline.

During my graduate days, I continued researching the relationship between society and technology, covering topics like nuclear technology, the COVID-19 pandemic, and information technology. I also developed educational programs on STS for graduate students.

Research in information technology inevitably impacts society

From the perspective of ELSI and RRI, which area are you currently focusing on the most?

Definitely information technology. I believe it has a unique nature compared to other fields of science and technology. Information is inherently intertwined with society, making it impossible to separate the two. In other words, ethical, legal, and social aspects are embedded in information technology right from the very beginning.

When we think of information technology, AI-related technologies are often the first that come to mind.

Many people worry about AI, fearing it could threaten their jobs and wages. But, are these issues truly caused by AI? Or are they long-standing societal problems merely coming to the surface?

When something goes wrong, we tend to think, “Maybe it’s because of new technology,” but this kind of thinking alone can obscure the real cause and distance us from finding effective solutions. I believe it’s essential to “reframe the problem,” and this is where an ELSI perspective becomes valuable.

I am particularly interested in issues that arise at the intersection of multiple fields. In the overlapping areas of life science and information sciences, for example, linking medical data with genome information holds vast potential for new applications. However, this could also raise concerns about privacy and other sensitive matters. Therefore, we need to approach these ethical and risk-related issues by considering the unique nature of both AI technology and genome science. Given the rapid pace of advances in both fields, which are highly specialized, addressing ELSI-related challenges in these boundary areas is a pressing concern for me.

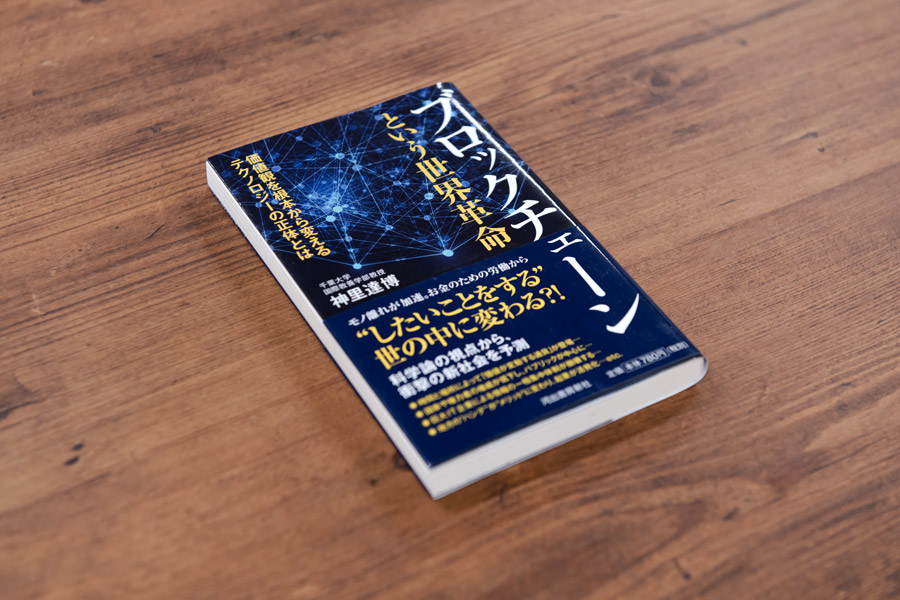

Another area I’m focused on is blockchain technology, which has the potential to create ‘trust’ and take over ‘administrative tasks.’ While public attention is still largely focused on cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, blockchain technology as a whole hasn’t been widely recognized for its transformative potential. Perhaps this is because it’s a technology so novel that even science fiction didn’t predict it. Nevertheless, I believe blockchain could significantly reshape how society functions.

The true intelligence lies in the ability to manage knowledge

Any message for students who are interested in ELSI and RRI?

ELSI and RRI are finally gaining increased attention in Japan, and I’ve received inquiries from people asking how they can conduct research while keeping these considerations in mind.

For young people interested in ELSI or RRI, I recommend first developing expertise in another field. Without a solid knowledge base―your ‘root,’ so to speak―it will be difficult to effectively collaborate across disciplines.

That said, ‘expertise’ today isn’t just about ‘accumulating knowledge.’ In an era where we can look up almost anything, memorization has become less valuable. What is truly important in a complex modern society, especially in fields like ELSI and RRI, is ‘the ability to navigate and apply knowledge’ effectively.

For example, how do you approach unfamiliar concepts or new ways of thinking? If you get too entrenched in a single field, clinging to the knowledge you’ve already acquired, you risk losing the broader, multifaceted view needed to tackle real-world problems.

I believe that true ‘intelligence’ in today’s world is the ability to contextualize one’s specialized knowledge, adapt to new developments, and continually update oneself. ELSI and RRI offer a space where these skills can be actively applied.

Across all fields, there is an increasing need for the ability to integrate and connect different types of knowledge. So, what does it mean to be truly intelligent? What is the ‘new liberal arts’ that our future requires? I believe universities must take the lead in refining how knowledge is understood and utilized.

Please tell us about your future research prospects.

Starting this year, I aim to explore the scientific basis of justice and investigation from an ELSI perspective. Researchers in psychology, anthropology, and related fields have long examined the limitations of eyewitness testimony and DNA testing. While these scientific methods can be invaluable, their misuse may result in wrongful convictions. Through my research, I hope to contribute to ensuring that science and technology are applied appropriately, ultimately promoting a just and fair society.

Recommend

-

Unfettered thinking, elaborate theorizing, and an accepting and positive attitude: With the precepts of his former supervisors in mind, Dr. Shimada is tackling the global food crisis

2023.01.04

-

Enigmatic Soliton Waves in Nature and Space: Demystifying Equations of Everyday Physical Phenomena

2023.12.04

-

The Global Goal of Carbon Neutrality by 2050 (Part 1): Universities as Agents of Change

2023.07.12