“I am exploring how to create a ‘route map’ for differential equations,” says Associate Professor Kazuki Hiroe of the Graduate School of Science, his face bright with enthusiasm.

By transforming differential equations into geometric figures, Associate Professor Hiroe aims to uncover relationships that remain hidden when these equations are confined to mathematical formulas. Differential equations belong to the abstract world of mathematics, while figures inhabit the visual realm of geometry. What remarkable insights might emerge when these two distinct worlds intersect?

“The fascinating thing about mathematics is its human element,” he says with a smile. We spoke with him about his current research and the exciting possibilities it opens for the future.

‘Rotating’ differential equations to transform them into figures

First, could you tell us about your research?

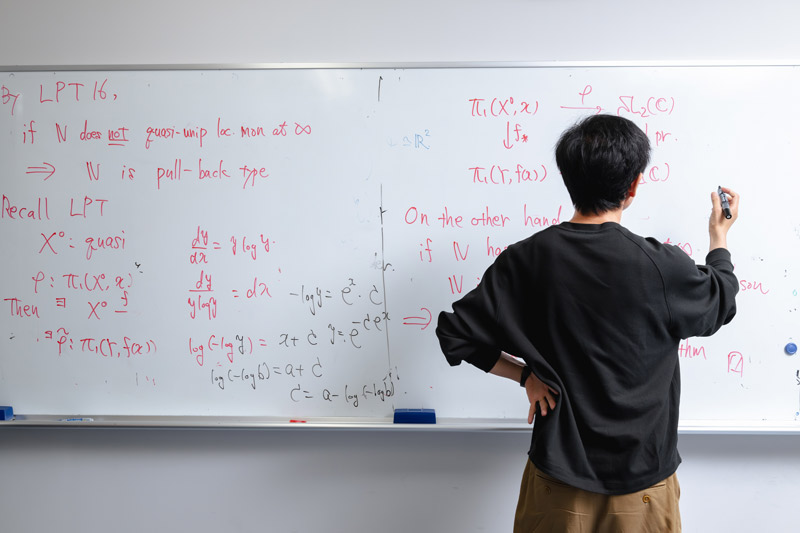

I am conducting research to investigate the relationships between various differential equations* by representing them graphically. Many mathematical objects, including differential equations, are inherently invisible. By expressing these equations as figures —graphs composed of points and lines—I aim to simplify their complexity and highlight their essence in a more comprehensible way.

*More specifically, his work focuses on ‘algebraic linear differential equations,’ a particular type of differential equation. The coefficients of this equation are expressed as polynomials, allowing for seamless application of various processes, such as mathematical manipulation and graphical representation, in an integrated manner.

This process is like ‘reaching into your pocket to retrieve a specific item.’ Even without looking inside, you can find what you need just by feeling its shape—whether it’s your keys or your wallet—because you already know what’s in your pocket and can recognize their forms (jagged, square, or otherwise). My research applies a similar concept to differential equations. Although these equations are invisible, I work to ‘interpret’ them as shapes, ‘classify’ these shapes, and visualize them from a new perspective.

How do you convert a differential equation into a diagram?

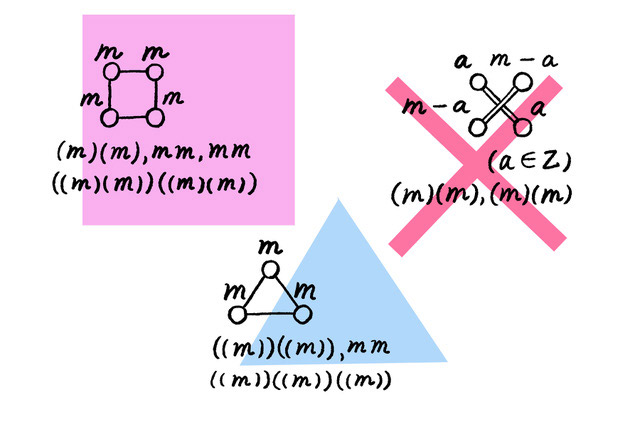

I use a property of geometric figures known as ‘rotational symmetry.’ This property means that when a figure is rotated by a certain angle, it retains the same shape shape as the original. For example, an equilateral triangle has ‘120-degree rotational symmetry’ because it looks the same after being rotated 120 degrees, and a square has ‘90-degree rotational symmetry’ because it maintains its shape when rotated 90 degrees. In other words, even if you don’t know the exact shape of a figure, you can predict its form to some extent by examining its rotational symmetry.

While rotational symmetry is typically associated with geometric figures, I became interested in the possibility that differential equations might also possess a similar geometric symmetry. By performing ‘operations similar to rotating a geometric figure’ on differential equations and examining their ‘rotational symmetry,’ I can uncover the hidden ‘shape’ of these equations. Of course, it is not possible to physically rotate a differential equation, so this involves applying a ‘mathematical transformation that corresponds to rotation.’

I am using this concept of rotational symmetry to explore ways to convert differential equations into geometrical forms and, conversely, to reverse the process—converting geometric forms back into their original differential equations.

‘Route Map’ Approach: Drawing a ‘route map’ of differential equations with moduli spaces as ‘stations’ to discover the simplest differential equation

What are the benefits of visualizing differential equations?

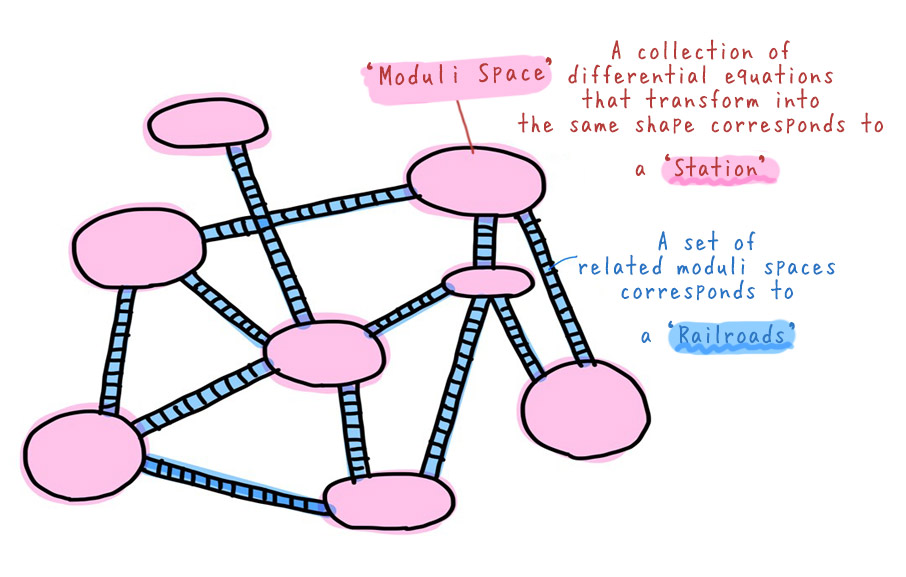

By representing differential equations graphically, we can group those that transform into the same shape into what is called a ‘moduli space.’ Furthermore, if one moduli space can be transformed into another, the two can be considered related. In other words, we can create a ‘railroad map of differential equations,’ just as the figure shown below, where moduli spaces serve as ‘stations’ and the relationships between them are represented as ‘railroad tracks.’

In this railway map, all the moduli spaces connected by the tracks share the same properties. In other words, by following the tracks to reach the moduli space containing the simplest differential equation and solving it there, you effectively solve the differential equations in all the moduli spaces connected by the tracks. This railway map is a powerful tool for finding ways to solve difficult differential equations.

Given the infinite number of differential equations, it would be impossible to draw a route map based solely on mathematical formulas. However, by grouping equations with similar properties and transforming them into geometric figures, it became possible to define stations (moduli spaces). The key insight of this research is that by using geometric figures, the relationships between differential equations, which were previously unclear from mathematical formulas alone, can now be made explicit.

I see, so this ‘route map’ is your achievement.

Yes, but not all differential equations can be converted into graphical representations using the current method. If I can expand the range of differential equations that can be transformed into graphical forms, I should be able to identify even simpler differential equations, as there would be more stations (moduli spaces) and tracks on the map.

I am currently developing new methods to relate moduli spaces to each other and will continue my research to create even more detailed route maps.

To which field do you think your research can be applied?

The moduli spaces of differential equations seem similar to the spaces encountered in particle physics. I hope there will be some connection to that field. It would be exciting to collaborate on research in the future.

Communication is the best part of mathematics

I understand that you were originally studying Engineering during your undergraduate years. Why did you transition to Mathematics in graduate school?

That’s because I wanted to fully understand the mathematics I was studying. I graduated from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in the Faculty of Science and Engineering, where I focused on atomic and molecular structures during my undergraduate years. However, the mathematics involved in these theories was extremely difficult, and I could barely understand it. As I progressed in my studies, I gradually became uncomfortable using mathematics which I didn’t fully understand as a tool. I began to feel that I would be better suited to an environment where I could learn the theory of mathematics itself. After much consideration, I decided to take the plunge and apply to the graduate school’s Department of Mathematics.

What do you find interesting about mathematics?

What I find fascinating about mathematics is that, unlike chemistry or physics, it doesn’t involve experiments. My research is primarily done with just paper and pen, relying solely on the human brain to create theories and identify errors. In such an environment, ‘communication between people’ plays a vital role.

Mathematics feels somewhat like a sport, where differences in individual abilities—such as speed and problem-solving power—are often quite apparent. When I transitioned into studying mathematics mid-career, the gap between my skills and those of my peers was striking, and at times, I felt overwhelmed. However, I was fortunate to be surrounded by supportive individuals. I actively engaged with mentors, classmates, and researchers from other universities, exchanging ideas and insights while conducting research. Through this, I discovered the joy of connecting with others. It is not uncommon for casual conversations with mathematicians I have never met to turn into deeply engaging discussions about mathematics. These aspects of human connection—what I might call a sense of humanness—are, to me, one of the greatest appeals of the field.

I want to utilize my background and interact with people from many different fields.

How do you plan to proceed with your research in the future?

Having transitioned into mathematics from another field, I aim to actively engage with disciplines beyond mathematics rather than limiting myself to its boundaries. My hope is to collaborate with researchers from various fields, including material science, which is where I originally began my academic journey. I would like to expand the network of connections I have cultivated in mathematics to foster interdisciplinary collaboration.

Finally, do you have a message for students and young researchers?

I encourage you to keep a broad perspective and not lock yourself into thinking, “This is my field of expertise!” As you progress from high school to university and eventually graduate school, you will inevitably choose a specialization. Please remember—there are countless fascinating research opportunities you may not yet know about. It would be a shame to limit your possibilities by being overly fixated on a single specialty.

Explore widely and try new things while you are young. Enjoy this vast and dynamic world of mathematics and embrace the opportunity to connect with people from diverse backgrounds.

● ● Off Topic ● ●

Since mathematics does not involve experiments, everything has to be carefully thought out by humans, right?

Exactly. And that’s what makes it so challenging—because even the slightest error can undermine an entire theory. I remember once thinking I had finally completed a theory. I went to bed feeling relieved, but I woke up suddenly at about 3 a.m. feeling uneasy. I could not shake the thought that something might be wrong, so I ended up sitting at my desk all night, searching for flaws until morning.

Do you think English is really essential when working with researchers from overseas?

Even if your English is not perfect, if you are doing interesting research, people will want to talk to you. Mathematics itself is like a universal ‘language’ that allows you to connect with researchers from all over the world. It is truly amazing.

Recommend

-

Creating Cities of Coexistence: Transitional Landscapes with the Tapestry of Diverse Lives

2024.02.09

-

Unraveling the Mysteries of the Feline Mind: Insights from Animal Psychology

2023.05.01

-

Navigating Offshore Wind Power Expansion: Nurturing Ocean-based Wind Energy Management Experts through Industry-Academia Partnership

2023.09.28